On February 19, 1942, when the Japanese Empire first attacked Darwin, Australia, killing 200 people, the necessity to keep shipping lanes open between the U.S. and our ally, Australia, became critical. This battle to maintain control of the South West Pacific waterways would spread across many islands and years.

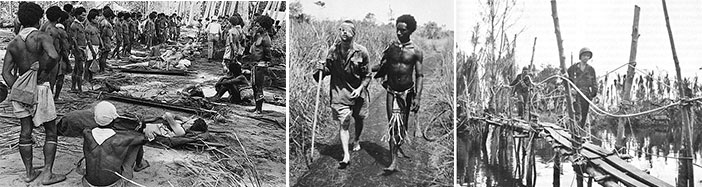

Three American GI’s lie dead on Buna Beach. The image was captured by George Strock on 31 December 1942 though it is sometimes described as having been taken in February 1943, a month after the battle ended. Life Magazine was finally able to publish it on 20 September 1943 after President Roosevelt authorized its release. It was the first photograph published in the United States during World War II to show American soldiers dead on the battlefield. Roosevelt was concerned that the American public were growing complacent about the cost of the war on human life.

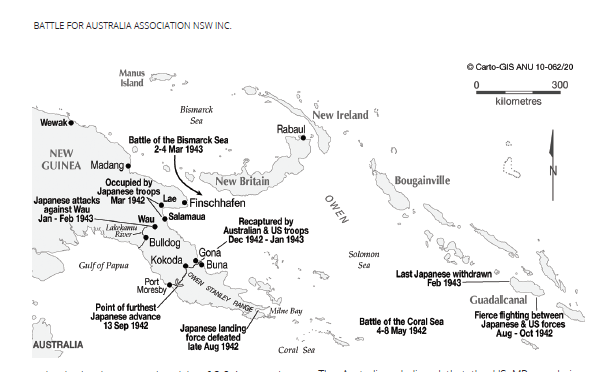

In 1942 the Japanese swiftly moved down the Island of New Guinea seeking control of strategic areas. Port Moresby, a short distance from the tip of Australia, became a major target. Along the way, the enemy forces set up several coastal bases such as Lae and Salamaua.

Between November 16, 1942 and January 22, 1943 the Allies recaptured vital beachheads in the Battle of Buna-Gona on the New Guinea coast. Almost 2,000 U.S. and Australia troops perished, while the Japanese suffered higher fatalities amounting to 7,000 men.

Battle of Buna-Gona on the island of New Guinea

Across the waters, numerous battles continued to rage in the Solomon Islands. Slogging through mud, hacking through jungles, breaching alligator infested rivers the fighting on Guadalcanal lasted six months and two days, from August 4, 1942 through February 9, 1943. U.S. Marines, Army, Navy and Coast Guard would bury 7,100. The Japanese death toll rose to 19,000. These figures did not reflect those wounded or sick with malaria or other diseases rampant in the jungles

As casualties mounted, in December of 1942, at Imperial General Headquarters, the Japanese decided to strengthen their South West Pacific Area holdings. They devised a plan to move 6,900 troops in early March from Rabaul, their major base at the North West tip of New Britain Island, across the Bismarck Sea to Lae on New Guinea.

When the U.S. learned of the Imperial Forces intent via U.S. and Australian codebreakers, they became alarmed. MacArthur needed to maintain control over these waters to regain the Philippines. With the use of decrypting machines such as ‘Magic’, the Allies were able to identify the path and dates the Japanese convoy expected to transport their 6,900 troops across the Bismarck Sea. Enemy movement observed by the Allies confirmed the decrypted messages. Reconnaissance planes observed 59 vessels gathering near Rabaul on February 22.

Due to two tropical storms passing through the area, the convoy was not detected until March 2nd. However, the Allies were ready. A variety of aircraft–heavy, medium and light bombers, along with fighter planes–with Australian and U.S. crewmen, led by the U.S., would depart from different bases. The new technique of ‘skip bombing’ would be employed. U.S. aircraft would dive low toward the broad side of a ship, releasing their bombs that would actually ‘skip’ across the surface of the water, striking the enemy ships at or below the waterline. This new manner of engaging in battle confused the Japanese, causing the convoy to break formation and become vulnerable. Enduring bombings and strafing’s during the day, PT boats were sent out at night to continue the assault. The results were catastrophic for the Japanese.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea would only last from March 2nd – 4th. However, over those two devastating days, all eight of the Imperial Japanese transports and four of their eight destroyers would be lost, along with nearly 3,000 men.

10 Americans died in battle and 3 to accidents. The new aerial attack technique of ‘skip bombing’ coupled with strafing proved highly effective.

MacArthur boasted, overstating wild claims of the success. A U.S. propaganda newsreel asserted the Japanese lost 102 aircraft, 15,000 troops, and 22 ships.

In truth, after the war, a Japanese officer stationed at Rabaul claimed nearly 20,000 men were lost transporting them from Rabaul to New Guinea. These facts greatly hampered the Imperial Forces continued presence in the South West Pacific.

Another significant bit of luck deriving from this battle happened later in March. As the Japanese attempted to escape, they landed on several of the smaller islands. One of those was Goodenough Island. Australian troops fought and killed a landing party arriving in two flat-bottomed boats. Inside the boats important papers were discovered sealed in tins. Once translated some of the documents detailed the names and postings of every Japanese officer in their Army. A gold mine. Copies of these vital documents were shared among the Allies throughout the Pacific Theater.

General Imamura, of the Imperial Japanese Army based at Rabaul, sent his chief of staff back to Imperial General Headquarters to report the horrific losses.

Upon hearing of the disaster, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto personally promised Emperor Hirohito he would revenge the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. Yamamoto planned ‘Operation I-Go’ for April of that year. It would be his last offensive of WWII.

Unaware the Americans were intercepting their messages the Japanese would, once again, lose more territory in the Pacific along with Admiral Yamamoto, their beloved leader who helped orchestrate the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea became a significant turning point in the Pacific Theater during WWII. The air power of the Allies delivered death in staggering numbers as luck rode their wings over the Bismarck Sea in a war that was far from over. It marked the beginning of the end for Japan, even though the Emperor would continue to wage war for two and one-half years longer until nearly depleted of munitions, food and soldiers.

World War II touched many shores, taking an estimated 80 million lives. War is ugly. No one wins. The bravery of the men and women who carried the burden of that struggle, who worldwide buried their loved ones, should never be forgotten.

Thank you to all who served, near and far, for our freedom.

Hi Denise; Thanks for sending this.

Do you remember meeting my grandson, Kyle ? He is now in the US Air Force, based in Germany, trained as a photo-journalist.

Tom