As the 353 Japanese aircraft rained death and destruction across the Island of Oahu, Takeo Yoshikawa, using his alias of vice-counsel Tadashi Morimura, was hurriedly burning his implicating files inside the Japanese Consulate on Nuuanu Avenue. The 13,400-square-foot grounds of the Japanese consulate, in a well-to-do neighborhood, displayed a gold imperial chrysanthemum crest outside the two-story main building where the smoke billowed from the chimney, as the pile of incriminating evidence was destroyed.

When the FBI arrived at the Japanese consulate around 9:30 to place Takeo and his accomplices, untrained spies, Counsul-General Nagao Kita, Kokichi Seki the acting treasurer, and other staff members under house arrest, they were too late. Early that morning Takeo had been listening to his short-wave radio and heard the secret code words “East-Wind-Rain” which carried the heavy weight of Japan announcing their planned attack against America. The FBI unearthed nothing that linked Takeo to his crimes.

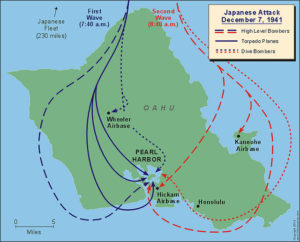

Yet, this 27-year-old vice-counsel had been in constant communication with Tokyo since his arrival on March 27 of 1941. When he first disembarked the Nitta Maru, accompanied by the new Japanese Counsul-General, Nagao Kita, he rented a second story apartment that overlooked Pearl Harbor. From this seven-mile distance he had a clear view of the American fleet at rest in port. His days were spent wandering the island, taking photos and notes of fleet movement and security preparations to report back to the Land of the Rising Sun. He flew in airplane tours, taking aerial photos of the U.S. installations such as the airfields at Wheeler and Ewa, he took the Navy’s own harbor tour, one night he dove under the waters of Pearl Harbor to see if there was a submarine net, donning work clothes he posed as a local and walked the outskirts of the airfields. He also employed local taxi drivers to scour the island including observing the layout of Kane’ohe Base and the Army’s Schofield Barracks. He was highly trained and efficient.

Takeo, a handsome man, who graduated at the top of his class in 1933 from the esteemed Etajima Imperial Japanese Naval Academy, wore his hair long and was a flamboyant dresser. His favorite place to observe the movement and activity at Pearl Harbor was a Japanese teahouse in the Alewa Heights section, the Shuncho ro (Spring Tide Resturant) on Makanani Drive. The teahouse not only provided strong drink, a cooperative Nippon owner, and geishas, but also a front window with an excellent view of Pearl Harbor, Ford Island, and the adjoining Army Air Corps base at Hickam Field. As luck would have it, the teahouse came equipped with a telescope or two.

On December 6th, Takeo sent his last cable to Admiral Yamamoto, the Imperial Navy Commander-in-Chief:

“Vessels moored in harbor: Nine battleships; three Class-B cruisers; three seaplane tenders; seventeen destroyers. Entering harbor are four Class-B cruisers; three destroyers. All aircraft carriers and heavy cruisers have departed harbor. No indication of any change in U.S. fleet.”

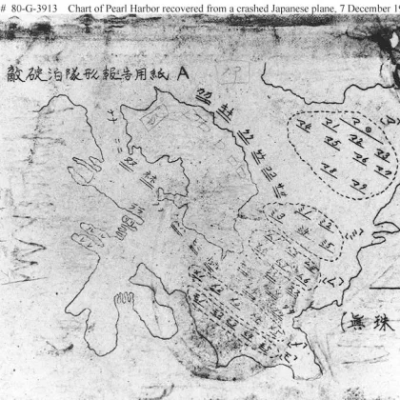

On September 24, 1941 a message sent from Tokyo to Takeo via Kita, asked that Pearl Harbor be divided into five distinct zones. He was to draw a “plot” or grid which detailed the exact placement and number of ships. In mid-November the youngest lieutenant commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Suguru Suzuki arrived in Honolulu on the Taiuo Maru with the explicit orders to confirm Takeo’s information regarding the American defenses and obtain more intelligence from Japan’s spies on the island. Suzuki passed a tiny ball of crumpled rice paper containing a list of 97 questions from command at Tokyo on to Takeo. In answering these question, Takeo provided all the essential information regarding the positions of the U.S. fleet at dock and security measures for the surprise attack. On December 6th Takeo sent his last cable containing precise ship locations, maintaining there were no out of the ordinary changes to the U.S. routine patrol exercises.

One of the 97 question posed, the most important, was on what day of the week would the most ships be docked at Pearl. His answer was Sunday.

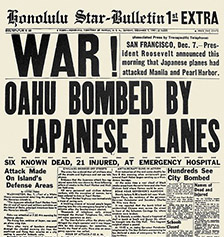

And that Sunday morning of December 7th 1941, a day President Roosevelt declared “a date which will live in Infamy”, Takeo Yoshikawa, the man who handed over the detailed map of the U.S. American fleet, was arrested. For approximately ten days, Takeo and the staff were confined to the consulate before being shipped to San Diego. Then in February of 1942 the Hawaii consulate staff arrived at the secluded Triangle T Ranch, a guest ranch in southern Arizona known to the wealthy for its privacy, an ideal setting for sensitive information gathering. The 23 detainees who occupied the small cabins, were guarded by Border Patrol agents with no outsiders, or the agents themselves, knowing the importance or identity of those sequestered. The FBI questioned them for weeks, but without discovering that Tadashi Morimura, was actually Takeo Yoshikawa.

J. Edger Hoover was anxious to prosecute, however, fearing retaliation against our American counsul abroad, the State Department refused. In May of that year the U.S. negotiated a large-scale prisoner exchange with Japan, which included those at the Triangle T Ranch. Ushering them to the Pennsylvania Hotel, where the New York police joined in guarding the prisoners, they boarded the Gripsholm, a neutral Swedish ocean liner, on June 18 and were sent back to Japan.

It was not until later that the FBI discovered Takeo Yoshikawa’s identity and treachery. Once safely back home, Takeo continued naval intelligence work for the remainder of the war. Then, in 1945, fearing being captured during the occupation, he fled to the mountains hiding as a Buddhist monk.

The United States had several warnings of the forthcoming attack though the highly secretive machine Magic which could decrypt Japan’s J-19 diplomatic code, the Purple Code, but were slow to piece it together. One stumbling block was the fact that the Hawaii consulate did not have a short-wave transmitter, so their messages back to Tokyo were sent from downtown Honolulu via the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and Mackay Radio and Telegraph, both commercial companies. Only RCA would cooperate with the FBI, thus U.S. intelligence only had half of the what would become known as the “bomb plot.”

In considering the preparations for war, the necessity for organized intelligence gathering spanned from the Hawaiian Islands, along the West Coast and into Washington D.C. After all, spying is one of the oldest, and in this case deadliest, occupations.

It is said that almost 60% of all causalities on December 7, 1941 were burn victims. It is important to remember those who passed on that first day of battle on Oahu and then in the Philippines, which drew us into an unwanted World War II. Over the course of the four-year struggle, approximately 418,500 military and civilian Americans gave up their lives for our freedom.

So, on this December 7th, a “date which will live in infamy,” let us give honor to all who suffered during a war that brought global death and destruction and pledge to teach peace.

Amazing research and information. Thank you, Denise

Thank you! Best of luck with your new book. Denise