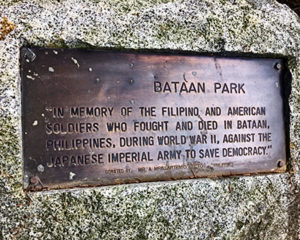

Having fought gallantly for four months, weak, starving, sick, exposed to the burning heat of the Philippines, roughly 60,000 Filipino troops and 11,000 – 15,000 men from the United States surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942 on the peninsula of Bataan. A fate that would claim 5,000-10,000 Filipino soldiers and about 650 American lives along the grueling march. The numbers vary due to the inability to get an accurate count of how many actually were captured at the largest surrender of American forces since the Civil War, coupled with those soldiers who were able to escape. While the numbers might differ, the manner in which the brutal slaughter of Prisoners of War occurred is documented and remembered on April 9, 1942 as the worst, most egregious, displays of inhumanity in the Pacific Theater during WWII.

Araw ng Kagitingan, Day of Valor, is currently celebrated with prayers and laying of wreaths at statues and plaques across America and in the Philippines commentating the thousands of souls lost to a hostile enemy. Manila was first attacked on December 8th 1941, with the international date line that was December 7th, 1941, in U.S. time, the same day as the attack on Pearl Harbor. Outnumbered, with ill preparation by General McArthur, the country of the Philippines was the last to surrender to the Japanese in Asia with the fall of Corregidor on May 6, 1942.

World War II in the Pacific was costly in lives, ships, tanks and artillery. The enemy, hardened by years of war with China, obedient to an Emperor Hirohito who was also seen as a God, who professed the superiority of the Japanese race with the goal of conquering all of Asia and beyond, created a fierce and unforgiving opponent. The Nippon way of life consisted solely to be given up in service for the Emperor. Death was equivalent to duty.

Many of the Imperial Japanese forces displayed a total disregard for the Geneva Convention (especially war related observances for prisoners). Some of the Japanese commanders at Bataan did not perceive their captives as POW’s, but viewed the courageous Allied soldiers, and 38,000 captured civilians, with total distain, and subjected them to various types of torture, including the “sun treatment,” sitting in sweltering heat with no protection for your head, or being stripped naked and forced to sit next to clear, cool water. If one asked for water, they were shot. Others were burned alive, subjected to random beatings, beheadings, bayonetting’s or mowed down by trucks. Without food and water many could not keep up the pace of the march and were murdered. At the tranquil setting of the Pantingan River an estimated 350-400 Filipino officers and those immediately under their charge, were executed after surrender.

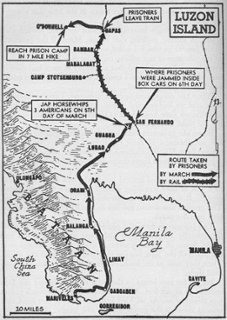

Once the prisoners reached the San Fernando railroad, they were stuffed into sweltering, unventilated metal box cars in 110-degree heat.

According to Staff Sergeant Alf Larson:

The train consisted of six or seven World War I-era boxcars. … They packed us in the cars like sardines, so tight you couldn’t sit down. Then they shut the door. If you passed out, you couldn’t fall down. If someone had to go to the toilet, you went right there where you were. It was close to summer and the weather was hot and humid… We were on the train from early morning to late afternoon without getting out. People died in the railroad cars.

Upon arriving at Tarlac, the captives marched another 12.5 miles to their interment at Camp O’Donnell where the death total continued to climb. Of the estimated 80,000 POW’s who began the march only 54,000 endured the 60 plus mile deadly struggle, spanning six days with little food, an occasional scoop of rice, to reach Camp O’Donnell.

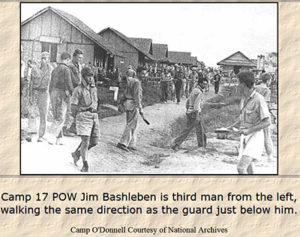

Yet, their fight for survival had just begun. At Camp O’Donnell they were crammed into overcrowded living conditions where, due to poor hygiene, dysentery and malaria spread quickly.

A report prepared by Colonel James W. Duckworth, Medical Corps, United States Army who commanded all hospitals in Bataan states:

In fact, conditions were so bad that, between the period of 15 April 1942 and 10 July 1942, there were 21,684 Filipino deaths, a mean average if 249+ per day, and 1,488 American deaths, a mean average of 17+ per day… an all-time high for the period was reached when there were 471 Filipino deaths and 77 American deaths [on the same day].

The atrocities and savagery of the Bataan Death March prepared by Major William E. Dyes, “The Dyes Report,” who had miraculously escaped, made his way to Australia and then back to the U.S., were kept “Top Secret” for over one year by President Roosevelt in order to have American sources and energy focus on the European Theater. It was not until January 27, 1944 that the public was informed by the US Government of the harrowing event. Life Magazine soon ran a featured spread of officers who had survived. The reaction by America’s was outrage and fury, fueling the fire to overcome the enemy in the Pacific.

In 1946 The Bataan Death March was judged as a War Crimes and General Masaharu Homma, commander of Imperial Japanese Army in the Philippines, was executed.

The heroes who lived through this notorious Death March should give us hope.

One man, forced to work on Japanese machinery, would daily put sand in the cuffs of his pants and quietly, facing death if discovered, put the sand into the mechanism so that one day, the Japanese equipment would seize up and be rendered inoperable. Hopefully, his defiant courage had an impact and saved Allied lives.

On April 9th, the Day of Valor, marks a time to pause and remember those who fought during WWII, who contributed in small and grand ways, to provide us the freedom we enjoy. For it is in remembering the cruelty of war that we seek to teach peace.

Courage is faceless, honor is achieved, and freedom is priceless ~ Denise Frisino

Sobering information, but important to know and remember. Thanks.